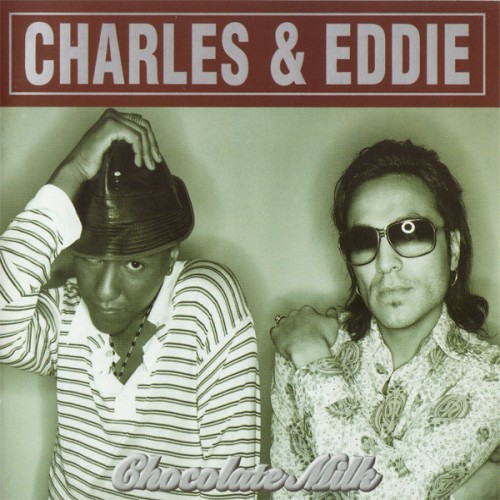

Charles Eddie Duophonic Rare

January 13, 1993,Section C, Page14Buy Reprints

View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 1992 Vinyl release of Would I Lie To You?

Singing Collectors

In the summer of 1990, Eddie Chacon was riding a New York City subway train when he spotted a young man across the aisle with a vinyl copy of Marvin Gaye's 'Trouble Man.'

'I had a hunch that to have that rare record on him, he most likely had to be a record collector like me,' Mr. Chacon said. 'I started talking to him about collections and we traded phone numbers. Neither of us knew what we were getting into.'

As it turned out, Mr. Chacon and the young man across the aisle, Charles Pettigrew, were also singers. Before long they formed the duo Charles and Eddie. Their debut album, 'Duophonic' (Capitol Records), includes their popular first single, 'Would I Lie to You,' and the recently released follow-up single, 'N.Y.C.' Mr. Chacon describes the album as a 'late 60's, early 70's classic soul-influenced record with a modern twist.'

'We're singing about contemporary issues,' Mr. Chacon said in a telephone interview from London, where the duo was on a promotional tour. 'But we're really drawing off the only thing we know how to do, the kind of music we've both been collecting since we were little boys, classic soul focusing mainly on soul crooners. This is the music that moves us.'

Growing up in Oakland, Calif., Mr. Chacon was influenced by artists like Mr. Gaye, Al Green, Isaac Hayes, the Chi-Lites, the Ohio Players and Sly and the Family Stone. Mr. Pettigrew, who was raised in Philadelphia and studied jazz singing at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, was a disciple of Johnny Harman, Nat (King) Cole and Little Jimmy Scott. Their professional relationship works because they are 'so compatible but so different,' Mr. Chacon says.

'He likes things he can apply his jazz flavorings to and that fit the smoothness of his voice,' he said of Mr. Pettigrew. 'I have a gritty voice and like lines with more aggression that I can get a little bit more loud with. We're attracted to different things in a song. Our working together evolves naturally, but it is all based on a solid friendship built on being record collectors of the same genre, of the same time period.' Making a Hit

What makes a good record producer? Patience and perseverance, said the producer and arranger Arif Mardin. He should know, having won four Grammy Awards and produced more than 40 gold and platinum records for a constellation of pop stars.

See All 14 Rows On Www.allmusic.com

'You can't be bored by repeated listenings,' Mr. Mardin, a vice president of Atlantic Records, said in a recent interview at his Manhattan apartment. 'And you have to think like a film director, even though you're working on a four-minute song. You have to think of what the lyric is saying and how to enhance it or bring out certain feelings in a particular song. If you get 100 percent from the artists, push them a little more -- drive them crazy -- just to see how fast that car can go before you get a ticket.'

After joining Atlantic Records in 1963, Mr. Mardin's first production assignment was with the Young Rascals. The song he produced, 'Good Lovin',' was a No. 1 hit in 1966 and earned a gold record. His other hits include 'Wind Beneath My Wings,' by Bette Midler; 'I Feel For You,' by Chaka Khan; 'Jive Talkin',' by the Bee Gees; 'Against All Odds,' by Phil Collins, and Aretha Franklin's 'Until You Come Back to Me,' 'Spanish Harlem,' 'Daydreamin',' 'Rock Steady' and 'Bridge Over Troubled Water.'

He also produced 'Where Is the Love,' by Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway; 'Set the Night to Music,' by Ms. Flack and Maxi Priest; 'Rainy Night in Georgia,' by Brook Benton; 'She's Gone,' by Daryl Hall and John Oates; 'Son of a Preacher Man,' by Dusty Springfield, and 'Pick Up the Pieces,' by Average White Band.

'The relationship between the artist and myself is very important,' he said. 'We must like each other and I must respect the artist's craft and vice versa. Once you go into this, it's almost like a marriage; you have to stay and finish and go through bad and good times, to feel that you're in the same boat and have to make this thing work.'

Mr. Mardin, who was inducted into the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame in 1990, is comfortable with a variety of music. Last year he composed 'Suite Fraternidad' in two movements, combining jazz, flamenco and Middle Eastern influences. It was performed last summer in Cologne, Germany, by the Westdeutscher Rundfunk Koln, or WDR Big Band. Joining the band were the American jazz musicians Peter Erskine and Steve Kahn as well as two Spanish performers, Carlos Benavent and Jorge Pardo. Mr. Mardin says he relies on basic compositional techniques when producing any type of music.

'I want to expose the melody, to have a lot of musical hooks so the attention is captured,' said Mr. Mardin, whose son, Joe, is also a producer, arranger and musician. 'I want to make the piece interesting, to grab the listeners and make them stay with me.' Brazilian Returns

The Brazilian art rocker Tom Ze's music has been called brilliant and skewed, intelligent and weird. Mr. Ze says his latest album, 'Brazil 5 -- The Return of Tom Ze: The Hips of Tradition' (Luaka Bop), was inspired by Tiffany glass and the mobiles of Alexander Calder.

'Calder because of the way each line in the songs is of different length and the way they go spinning from one line to the next meaningwise,' he said in a three-way telephone interview from his home in Sao Paulo. (The third party was one of the album's producers, Arto Lindsay, who was the interpreter.) 'And I was looking at a catalogue with many details of stained glass windows,' Mr. Ze added. 'I like the cut glass.'

Although highly regarded by critics and musicians, Mr. Ze says that 'there is no space for my music' in Brazil's music industry. He says he was frozen out commercially in 1973, when he recorded the experimental 'Todos os Olhos' ('All the Eyes'). The experience left him so resentful, he said, that for a long time he refused to listen to music.

'I didn't want to hear it because it made me feel so bad,' he said. 'People of my generation who I had made music with were being played on the radio, and I would tremble with fear thinking someone would recognize me and say: 'Why aren't you singing. Why don't we hear you on the radio?' So I got more interested in things outside of music: science, history, literature.'

But in late 1988, the pop star David Byrne bought a 1976 album of Mr. Ze's, 'Estudando O Samba' (Studying the Samba), while visiting Rio de Janeiro. He got in touch with him, and Mr. Ze eventually began recording for Mr. Byrne's Luaka Bop label and gaining North American exposure. Fungilab viscometer manual muscle.

'Old habits are hard to change,' Mr. Ze said, 'but since I started recording again I do listen to music occasionally without it being so painful.'